What Cultures Might Encounter Similar Issues When Trying to Visit a Newborn Baby in a Hospital

- Research commodity

- Open Access

- Published:

Beliefs and practices during pregnancy, mail-partum and in the outset days of an infant'southward life in rural Kingdom of cambodia

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth volume 17, Article number:116 (2017) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to record the behavior, practices during pregnancy, post-partum and in the commencement few days of an infant'southward life, held by a cross section of the community in rural Cambodia to decide beneficial community interventions to better early on neonatal health.

Methods

Qualitative study design with data generated from semi structured interviews (SSI) and focus group discussions (FGD). Data were analysed by thematic content analysis, with an a priori coding construction adult using available relevant literature. Further reading of the transcripts permitted additional coding to be performed in vivo.

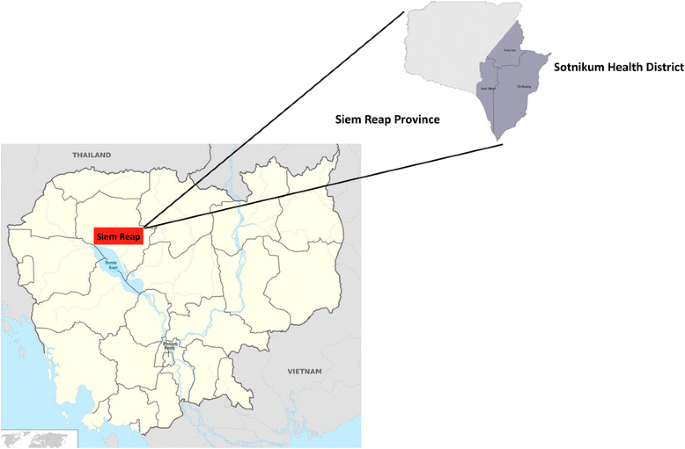

This study was conducted in two locations, firstly the Angkor Hospital for Children and secondarily in v villages in Sotnikum, Siem Reap Province, Cambodia.

Results

A total of xx participants underwent a SSIs (15 in hospital and five in the community) and six (iii in infirmary and three in the community; a full of 58 participants) FGDs were conducted. Harmful practices that occurred in the past (for example: discarding colostrum and putting mud on the umbilical stump) were non described as being proficient. Village elders did not enforce traditional views. Parents could describe signs of affliction and felt responsible to seek care for their child even if other family members disagreed, however participants were unaware of the signs or danger of neonatal jaundice. Price of transportation was the major barrier to healthcare that was identified.

Conclusions

In the population examined, traditional practices in late pregnancy and the post-partum period were no longer commonly performed. However, jaundice, a potentially serious neonatal condition, was not recognised. Community neonatal interventions should be tailored to the populations existing practice and knowledge.

Groundwork

Globally the proportion of childhood deaths that occur in the neonatal menses is increasing [ane]. Since 1990 there has been a 47% reduction in deaths in children less than v years of age [2]. Nonetheless, this rate of reduction has not been seen in infants 4 weeks of age or younger. It is estimated that 2.9 million neonates die each year, with one million of these occurring on the start day of life [three]. Globally neonatal mortality now makes up 44% of all deaths in children younger than five years [3]. The reasons why the fall in neonatal bloodshed has not mirrored that seen in babyhood mortality are complex. Ane proposed explanation is that interventions that have been successfully employed to reduce childhood death exercise non reach the community, where most neonates die [4, 5]. Another perceived bulwark to providing neonatal care, especially in remote areas, is the misconception that neonatal care is difficult and expensive [vi]. During the pregnancy and the postpartum period, perhaps more than at any other time, there are deep rooted health practices and behavior [7, 8]. Some of these practices are potentially harmful to the neonate and should be addressed in the communities where they occur.

Cambodia has ane of the highest neonatal mortality rates in Southeast Asia. In add-on, due to the lasting effects of civil war, at that place is a lack of trained healthcare providers, particularly in rural areas. The neonatal mortality rate is three times higher in rural areas than in urban areas [9]. In improver, at that place are but 2 functioning neonatal intendance units in the land and neonatal medicine is non nationally recognised as a speciality.

Understanding community do and beliefs is a vital pace in improving early neonatal outcomes as identifying knowledge gaps and harmful behaviour would allow community based programmes to be tailored to demand. There is a paucity of data regarding practices and beliefs during the late stages of pregnancy and in the post-partum period in Southeast Asia [10]. Geographically representative data is important to be able to improve health care provision in the early mail service-partum menstruation.

Methods

This qualitative study was conducted in two parts. The start was based at the Angkor Hospital for Children (AHC), Siem Reap, Cambodia [11]. Semi structured interviews (SSIs) were conducted with mothers to examine maternal behavior and FGD were conducted with other groups to enrich this data and obtain a general view of the population'south tradition beliefs around the time of childbirth.

All SSIs and FGD were conducted in Khmer by two trained Khmer field staff. For both the SSI and FGDs 1 of staff conducted the SSI or the FGD and ane member of staff took notes (topic guides for the SSI and FGD can exist seen in Additional files 1 and 2). Both sat together afterward and completed a contact summary sheet detailing nonverbal communication that occurred and meaning points arising.

Xv SSIs with mothers from rural areas whose babies had been admitted to the neonatal unit were conducted over a three-month catamenia. Questions concerning traditional practices, current practices and explanations of issues were asked around four areas: nascency, the newborn period, neonatal disease and healthcare seeking were discussed. Examples of questions included:

"Do you lot know of whatever problems that can happen to a woman during labour and childbirth?"

"Are at that place whatever special things that must be done subsequently a baby is born?"

"How practise you know a newborn infant is healthy?"

"Whose responsibility is it to make up one's mind whether to take a sick baby for assist?"

Mothers were selected using convenience sampling and had babies, who were medically stable but admitted to the neonatal unit. The study was explained to them and written consent obtained. Besides at AHC, focus group discussions (FGD) were conducted with 3 separate groups: grandmothers, fathers and healthcare workers. Fathers and grandmothers who participated in the FGD were also chosen by convenience sampling: they all had children or grandchildren admitted to AHC.

Following analysis of the infirmary-based SSI and FGD the topic guides were amended to ensure capture of the emergent themes. A farther five SSI were conducted with mothers of infants and three FGDs with customs healthcare workers and village elders. The SSIs and FGDs were conducted in Sotnikum, a rural commune located in Siem Reap Province, 1 of the poorest provinces in Kingdom of cambodia (Fig. i). Participants were called from rural areas using convenience sampling. During the report period a neonatal mortality village survey was beingness conducted by the study squad, during the form of this survey villagers were invited to participate.

Map of Cambodia showing Siem Reap Province with Sotnikum Health district highlighted in grey (map adjusted from Wikimedia commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cambodia_location_map.svg)

Data direction and analysis

All SSI and FGDs were vox recorded, translated (for pregnant) and transcribed into English: the interviewer checked the transcripts against the recording to ensure meaning had been captured. The principal investigator (PI) then read the transcripts, checking the English was correct. Ambiguous or unclear linguistic communication was discussed by the interviewer and PI until a consensus was reached. All data was imported into N-Vivo 10 (QSR International, Cambridge, MA). Coding was performed using a framework/thematic assay by all members of the study team. Afterwards translation the Khmer field workers and PI re-examined the transcripts, using the observational notes and vocalization recordings to inform the coding structure and to ensure confirmability and dependability. The analytic arroyo taken was informed by the research question: to explore the beliefs and practices during pregnancy, post-partum and in the first days of an infant'due south life in rural Kingdom of cambodia.

Prior to the SSIs or FGDs a short socioeconomic questionnaire was completed by Khmer field workers who recorded participants verbal responses. These data wereentered into an Admission 2003 database (Microsoft) and systematically checked for errors. These information were analysed using Stata/IC 12.1 (StataCorp, Higher Station, Tx, USA). Continuous variables were described by the median and range.

Ethics statement

Upstanding approval was obtained from the Cambodian National Ethic Committee for Wellness Research (0244 NECHR), the Oxford Tropical Inquiry Ethics Committee (535–xiv) and the AHC Institutional Review Board (676/fourteen).

Results

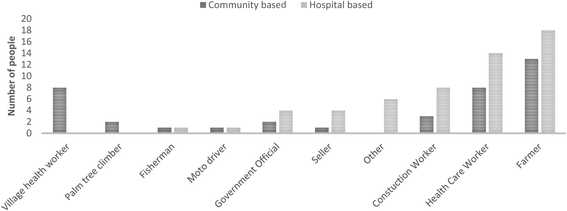

A total of xx SSIs (15 in hospital and five in the customs) and six (3 in hospital and iii in the community: total 58 participants) FGDs were conducted. Socioeconomic characteristics are shown in Table 1 and Fig. 2.

Graph showing occupation by hospital and community groups (a seller is a minor market trader, usually of household goods, a palm tree climber is someone who scales palm trees to harvest its fruits or sap which is refined into sugar)

Mothers

Traditional practices during pregnancy, such as food restriction, were not universally skilful. All the same when they were they typically focused on the female parent. When interviewees were asked why these practices were for mothers and not babies a common response was that the baby was not unwell but that the female parent was in danger of being sick, therefore the female parent needed aid every bit the baby was reliant on the mother.

"When deliver successfully, babe don't go danger. Merely for the mother information technology tin be dangerous." [Grandmother]

Traditional medicine was commonly described equally being used at two time points, one month earlier birth, to help the baby to exist built-in more easily and postpartum to increment breast milk production and prevent Tos. Tos has no translation in English. It is a physical and or psychological condition that postpartum women can suffer from if they swallow the wrong food, partake of wrong actions, thoughts or emotions or injure themselves. The described symptoms of tos range from collapse, seizure, locked jaw, "madness" to intestinal pain and diarrhoea. Use of different plants were described, nigh of which were brewed in hot water to make a tea.

None of the women interviewed described food restriction in pregnancy. In fact, weakness and hard labour was blamed on not eating enough during pregnancy and women described eating more so they would be strong to deliver their babe.

"We take to eat plenty food during pregnancy to brand the baby strong. We take to eat nutritious food" [Mother]

Nascency and post-partum

Where mothers chose to take their babies was discussed in the FGDs and SSIs. The majority of women reported that they felt that a baby should be delivered in a health facility. A common reason given for this was the Cambodian governmental policy to stop women delivering at home with a traditional midwife.

"yes, a traditional midwife can exist arrested at whatever time if they deliver the infant. If they still insist to deliver with a traditional midwife and if health center staff know nigh it the traditional midwife volition be sued. Then, when our baby gets sick and bring to the health center, the health centre staff will not take whatsoever responsible if there is a problem." [Father]

A few mothers mentioned that they needed to go to the health centre four times during pregnancy to get a check-up.

Many of the interviewees and FGD members and said that the umbilical string was for the baby to breathe through and to get nutrient by sucking on it. In that location was no description of using anything other than scissors to cut the string and none of the mothers had used traditional medicine on the cord although 1 female parent did describe an old exercise of using a paste made from a wasp's nest on a child'southward umbilical cord stump. Here a mother recalls instructions she has been given by the midwife and how this conflicts with traditional beliefs:

"The midwife asks united states non to put anything on the umbilical cord because it might cause problems to the infant. Just traditional midwife tell me to put some soil from the roof [wasp nest] on the umbilical stump to heal it" [Mother]

All of the mothers said that a baby should be fed directly after nascency and that colostrum should not exist discarded, although a few did mention that this had been the practice in the by.

"After nascence we get-go chest feeding the baby. Fifty-fifty though mother's chest not withal produce milk. We allow baby to suck on the breast to stimulate in order to quickly have milk" [Healthcare worker]

Traditional beliefs

Not all of the mothers interviewed held traditional behavior. Some mothers did non take traditional medicine or comport traditional ceremonies and professed a greater conviction in modern medicine rather than traditional medicine.

Some women described having mod medicine during birth and then using traditional medicine when that had finished. Traditional medicine consisted of unlike plant leaves, bark and roots. There were likewise a number of mothers who said that they had used traditional medicine in an earlier pregnancy simply were now only using modern medicine. One caption for this was that for the first babe the female parent doesn't know what to practise, so will therefore mind more to elders, in particular her mother. Notwithstanding, in subsequent pregnancies she will have more confidence, knowledge and experience then "goes her own way" moving towards modernistic medicine although may continue to use some traditional medicine.

"These days we trust modern medicines more than "Central khmer" traditional medicine. We nevertheless use a fiddling bit to keep our traditional habit." [Mother]

At that place was a harmonious balance in families equally well as individuals between the use of traditional and mod medicine. Grandparents were asked whether they minded if their daughters did not utilize traditional medicine during pregnancy or postpartum. In that location was a sense of tolerance for their daughters using mod medicine.

"Yes, traditional medicine. I remember a lot in the past. Nowadays, lodge is irresolute then much and so quick, therefore, traditional medicines have been lost and I have forgotten. Our social club nowadays, when woman is in labour pain, health centres are widely used. So, we don't depend upon on those kinds of traditional medicines." [Grandfather]

Neonatal Illness

The mothers who were interviewed could describe signs of a healthy or unwell babe.

"When the baby is healthy they can suck very well, they can sleep a lot and their skin colour looks overnice and fresh. But if they are non well they will not suck well, they cannot sleep, cry a lot and their body is thinner and pale" [Mother]

One exception was the recognition of jaundice. All of the mothers whose baby had been admitted to hospital for the handling of jaundice said they were surprised about the diagnosis and had not heard of it in a baby earlier.

"Like my baby, when she was built-in and her skin was yellow, nosotros thought that she is pretty and await lovely. Only I don't know it was an affliction" [Mother]

The main barrier to seeking healthcare was the cost of transportation, a one-way journey from rural areas of the health district to the referral hospital can cost up to $60. One respondent recalled the instance of a baby who died in his village because the parents couldn't find the money for transport

"That'due south correct. If cannot borrow from anyone and then would sell something. If nosotros have cow, we sell cow yes. And some of them do not take money and cannot take their babies to infirmary, and then dice" [Father]

Well-nigh interviewees said they would have a ill baby straight to a infirmary or health eye. Although the decision to have a baby for medical treatment was described equally being a family conclusion women felt empowered to be able to make the conclusion themselves even if other family members disagreed.

"Is that transferred immediately afterward you lot were told to or you take to expect to discuss with your family member first?

"No transfer immediately" [Mother]

Word

Amongst those interviewed in this study, there was a stated move abroad from harmful practices that were conducted in the past such as nutrient restriction, discarding colostrum, putting mud on the umbilical string. The lack of nutrient brake is different from the do described in neighbouring Laos where food restriction occurs early in pregnancy [12]. Most mothers said that they had had antenatal intendance, took iron supplements during pregnancy and had a facility based birth. The older generation seemed very accepting of this change. This differs from like studies conducted in Ghana and Indonesia where grandmothers made healthcare decisions and enforced traditional practices [vii, 13]. The reasons for this are likely to exist complex. However, Cambodia's traumatic history probably plays an of import part. One third of Kingdom of cambodia'southward population was killed during the Khmer Rouge era, it is likely that knowledge of traditional medicine and practices was lost during this period potentially leaving a vacuum that modernistic cognition and recommended practices have filled. For healthcare planners this is vital. This cognition tin be used to build relevant programmes, channelling scarce resource to teaching what is needed as opposed to imparting messages that are already known. For instance in this population promoting early essential newborn care in healthcare facilities where mothers give birth [14].

The signs of a sick neonate were universally known, with the exception of recognising jaundice. Globally neonatal Jaundice is an important cause of neonatal morbidity and mortality. It is a common reason for hospital access in the offset week of life worldwide and ane of the most mutual reasons for neurodevelopmental damage in developing countries [15–17]. Customs based interventions for the recognition and handling of neonatal jaundice has the potential to be benign in this population.

In that location was no sense that medical assistance should not be sought, even from the poorest of the participants. Parents categorically stated that they would seek medical help even if opposed by the older generation. Proportion of arraign to the mother for their child's disease did non occur. Unlike that depict in a study conducted in Ghana which identified a meaning influence by customs members on health seeking behaviour and a frequent theme of blaming mothers for their infant's affliction [7]. The bulk of participants stated that sick neonates must be taken to healthcare facilities for treatment and not treated at domicile or by traditional healers. The cost of transportation was stated as a major barrier and that delays in taking the neonate to healthcare facility were due to families trying to raise money to brand the journey. A written report conducted in Uganda examined the reasons that newborn infants in that location die, to do this they used a modified three delays model. This was comprised of delays in problem recognition or in deciding to seek care, delays in receiving intendance in a healthcare facility and delays in transportation. The authors ended that household and healthcare facility related delays were the major contributors to neonatal mortality [18]. Again this is a very relative point for neonatal healthcare policy makers. The focus of such programmes in this expanse should exist on transportation systems rather than instruction parents to recognise ill neonates.

Throughout the interviews and FGD it was credible that grandmothers were involved in the intendance of their daughters and daughters in law during pregnancy, kid birth and postpartum. However, there was no sense of dominance. Indeed, mothers seemed able to decide themselves whether to have traditional medicine or to partake of traditional practices, although some mothers, particularly for their commencement child, took and followed communication from the older generation.

The approach taken in choosing participants who had children admitted to hospital at the time of the study does accept limitations. Drawing general conclusions from this group could potentially be problematic as this a group who have actively sort modern medicine. However no difference was apparent in beliefs and practices between groups participating in the report at the hospital and those participating in rural areas.

Conclusions

In the population examined, traditional practices in late pregnancy and the post-partum menstruation were no longer usually performed. Still, jaundice, a potentially serious neonatal condition, was non recognised. In this community neonatal interventions tailored to the recognition and treatment of neonatal jaundice have the potential to reduce neonatal morbidity and bloodshed.

Abbreviations

- AHC:

-

Angkor Infirmary for Children

- FGD:

-

Focus group discussions

- PI:

-

Principal investigator

- SSI:

-

Semi structured interviews

References

-

WHO. Accountability for maternal, newborn and child survival: the 2013 Update. WHO press; 2013.

-

Progress Towards Millennium Development Goal 4: key facts and figures. September, 2013 [http://www.childinfo.org/mortality.html]

-

Levels and trends in child mortality. Estimates developed by the Un Inter-agency Group for Child Bloodshed Estimation. Written report 2013

-

Rosato M, Laverack G, Grabman LH, Tripathy P, Nair North, Mwansambo C, Azad K, Morrison J, Bhutta Z, Perry H, et al. Community participation: lessons for maternal, newborn, and kid health. Lancet. 2008;372(9642):962–71.

-

Lawn JE, Cousens S, Zupan J. iv one thousand thousand neonatal deaths: when? Where? Why? Lancet. 2005;365(9462):891–900.

-

Turner C, Carrara 5, Aye Mya Thein Northward, Chit Mo Mo Win N, Turner P, Bancone Thousand, White NJ, McGready R, Nosten F. Neonatal intensive care in a Karen refugee camp: a four year descriptive study. PLoS One. 2013;eight(eight):e72721.

-

Engmann C, Adongo P, Aborigo RA, Gupta M, Logonia G, Affah One thousand, Waiswa P, Hodgson A, Moyer CA. Infant illness spanning the antenatal to early neonatal continuum in rural northern Ghana: local perceptions, beliefs and practices. J Perinatol. 2013;33(6):476–81.

-

Herlihy JM, Shaikh A, Mazimba A, Gagne N, Grogan C, Mpamba C, Sooli B, Simamvwa Yard, Mabeta C, Shankoti P, et al. Local perceptions, cultural beliefs and practices that shape umbilical cord care: a qualitative study in southern province, zambia. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e79191.

-

MOH. Cambodia demographic and health survey 2012. 2010.

-

Herbert HK, Lee Air-conditioning, Chandran A, Rudan I, Baqui AH. Care seeking for neonatal illness in depression- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2012;9(3):e1001183.

-

Angkor Hospital for Children [http://angkorhospital.org/]

-

Alvesson HM, Lindelow One thousand, Khanthaphat B, Laflamme L. Changes in pregnancy and childbirth practices in remote areas in Lao PDR within 2 generations of women: implications for maternity services. Reprod Health Matters. 2013;21(42):203–11.

-

Sutan R, Berkat Due south. Does cultural exercise affects neonatal survival- a instance command written report among low birth weight babies in Aceh Province, Republic of indonesia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14(i):342.

-

WHO. Activity plan for healthy newborn infants in the western pacific region (2014–2020). 2014.

-

Olusanya BO, Akande AA, Emokpae A, Olowe SA. Infants with severe neonatal jaundice in Lagos, Nigeria: incidence, correlates and hearing screening outcomes. Tropical Med Int Wellness. 2009;fourteen(3):301–10.

-

Slusher TM, Zipursky A, Bhutani VK. A global need for affordable neonatal jaundice technologies. Semin Perinatol. 2011;35(3):185–91.

-

Bhutta ZA, Darmstadt GL, Hasan BS, Haws RA. Community-based interventions for improving perinatal and neonatal wellness outcomes in developing countries: a review of the prove. Pediatrics. 2005;115(ii Suppl):519–617.

-

Waiswa P, Kallander K, Peterson S, Tomson One thousand, Pariyo GW. Using the three delays model to understand why newborn babies die in eastern Uganda. Tropical Med Int Health. 2010;xv(8):964–72.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to extend their thanks to the staff working in the neonatal unit of measurement at the Angkor Hospital for Children and to the all the participants enrolled into this study.

Funding

This report was funded past a Wellcome Trust Strategic Honour (096527) awarded to Professor Michael Parker.

The funding trunk had no input in the blueprint of the study and collection, analysis, and estimation of information and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Information and materials are available on asking to the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

CT: Conceived the study, conducted the analysis and drafted the manuscript. SP: Conducted the SSI and FGD and made substantial contributions to the analysis and interpretation of the information. Critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. KS: Conducted the SSI and FGD and fabricated substantial contributions to the analysis and estimation of the data. Critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. LN: Facilitated the SSI and FGD and made substantial contributions to the analysis and estimation of the data. Critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. ND: Made substantial contributions to the design of the report. Critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. MP: Fabricated substantial contributions to the design of the report. Critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. PK: Fabricated substantial contributions to the design of the study and the analysis and interpretation of the data. Critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors accept read and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they take no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicative.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from the Cambodian National Ethic Committee for Health Research (0244 NECHR), the Oxford Tropical Research Ethics Committee (535–xiv) and the AHC Institutional Review Board (676/14). Written informed consent was taken from each participant prior to involvement in the report.

Publisher's Annotation

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Writer information

Affiliations

Respective writer

Additional files

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed nether the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/four.0/), which permits unrestricted apply, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided y'all requite appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Artistic Commons license, and betoken if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/ane.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

Near this commodity

Cite this article

Turner, C., Political leader, S., Suon, K. et al. Behavior and practices during pregnancy, post-partum and in the first days of an baby'southward life in rural Cambodia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 17, 116 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1305-9

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/ten.1186/s12884-017-1305-ix

Keywords

- Neonatal

- Pregnancy

- Postpartum

- Beliefs

- Healthcare

- Qualitative

- Kingdom of cambodia

baierauntudgeou1964.blogspot.com

Source: https://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12884-017-1305-9

0 Response to "What Cultures Might Encounter Similar Issues When Trying to Visit a Newborn Baby in a Hospital"

Post a Comment